Why 'Man With A Movie Camera' Is Considered The Best Documentary

Dsiga Vertov's 1929 experimental silent film tops Sight & Sound's lists of the best documentaries of all time according to critics and filmmakers.

It’s not surprising that film critics consider Man with a Movie Camera to be the best documentary of all time (via Sight & Sound). Film critics love films about the movies, especially when they’re metatextual and reference aspects of cinema and filmmaking that they understand better than most audiences. Dsiga Vertov’s 1929 film should be accessible to everyone — its introduction indicates the intention of “an authentically international absolute language of cinema,” that is to say a universal visual language, and its broad scope on everyday life is still relatable — but the focus on the crafts of filmmaking hinders its wider appeal because most people don’t care about such self-indulgently self-referential details of how movies are made.

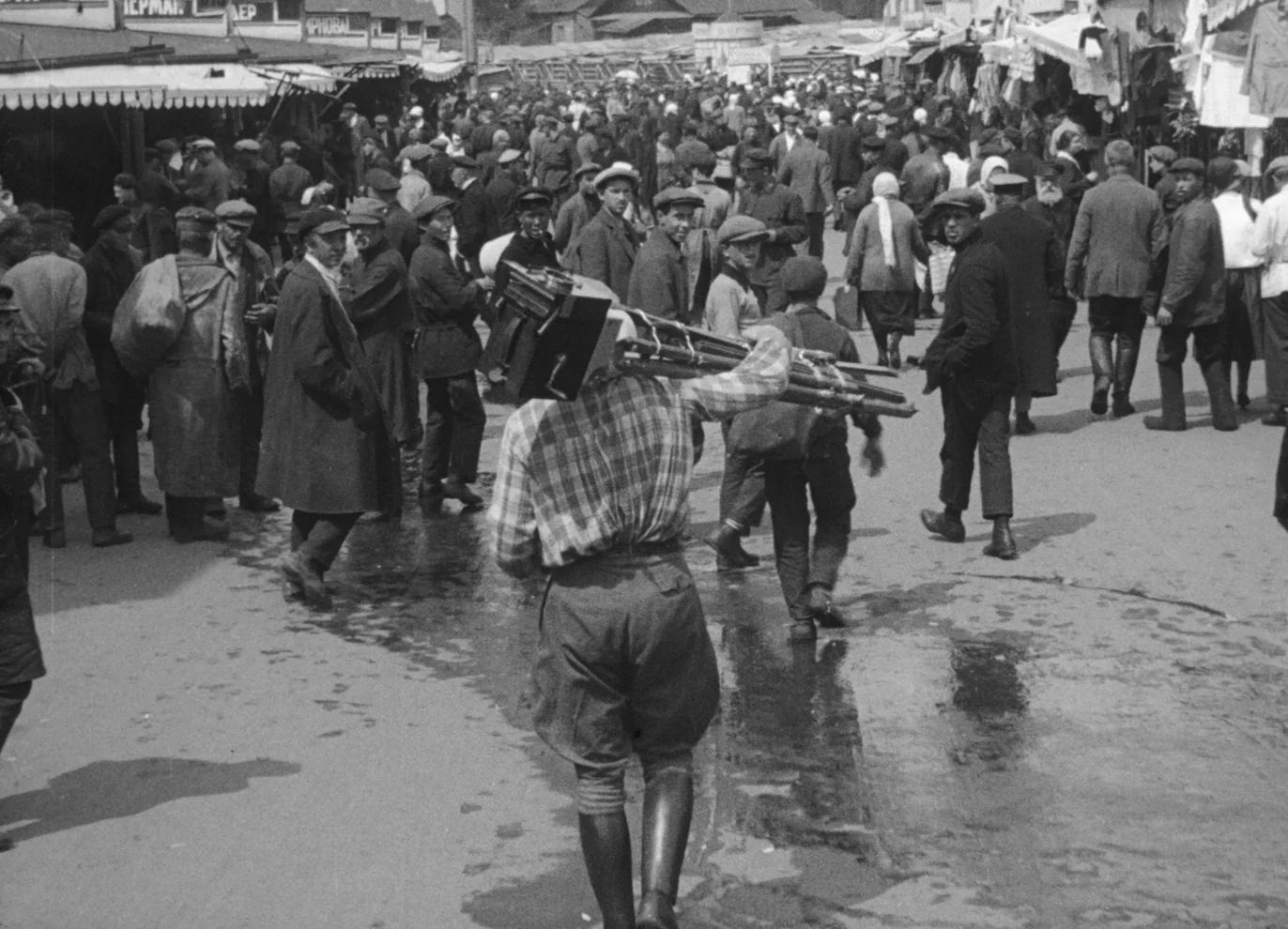

Man with a Movie Camera is full of such ironies. Vertov meant for it to be a nonfiction work, and the film immediately claims to have no scenario or actors. Yet, there is a scenario: a man with a movie camera films daily life in the Soviet Union. The film also features actors, or at least roles that are staged, including Vertov’s brother, cameraman Mikhail Kaufman, as the titular figure. The film was criticized by leading creators and scholars of both fiction and nonfiction cinema for its experimental elements fitting neither. To the world at the time, the film existed somewhere between and outside of dramatic and documentary modes.

Even by today’s standards, “purists” would probably disqualify Man with a Movie Camera as a documentary film. There’s not a lot of truth within it — or outside of it. It gives a sense of a single metropolis, like city symphony films, but it was shot in multiple locations around the Soviet Union, including Moscow and Kyiv. Meanwhile, there’s an acceptance that this was a pioneering work that introduced several cinema techniques. Rather, it’s a culmination of photographic and editing tricks that Vertov, Kaufman, and Vertov’s wife, editor Yelizaveta Svilova, had developed and honed over the previous decade with their Kino-Pravda newsreels and 1924 feature Kino-Eye.

One technique used very sparingly (maybe just the one shot of the chess game?), is reverse action. That makes sense if indeed the intent here was to present real life, as the reverse effect employed to turn beef into cow and bread into dough in Kino-Eye is a kind of cinematic time travel and an artistic challenge to the natural world. While it’s an interesting concept and shows the medium’s capability for manipulating reality, it wouldn’t belong in a film documenting actual life. Man with a Movie Camera is all forward motion, even in the cases of freeze frames and stop-motion shots. It’s a film of progression in terms of what’s on screen and how it’s being shown.

The most literal footage consists of daily activities, from awakening and getting dressed in the morning to transportation by cable car, automobile, and train, and work in factories and mines. There are also a lot of shots of leisure activities, including sports, games (including a shoot-the-Nazi game), exercise, rides, beachgoing, drinking, dancing, and playing music. And there are shots of life events: births, marriage, divorce, funerals. On top of all this, though, are the filmmaking and film exhibition sequences. Man with a Movie Camera is about the filming of these daily and leisure activities, the editing of that footage, and the exhibition of that material. If we look at the overlying structure, we see an audience filling an auditorium watching a film where the camera is looking at another camera that’s looking at real everyday life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nonfics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.